William Peel (1788 - 1866)

Peel was born on 14 June 1788 to Jonathan Peele and Sarah Smith. The family appears to have lived near Laycock, an ancient village west of Keighley in West Yorkshire. They did not originate there but may be traced back to the mid 16th Century in the Kildwick area: a Roger Peele was recorded as a Householder of Glusburne in 1657. He may have occupied Glusburn Old Hall or a farm in the Glusburn Green / Ryecroft: properties here were linked to members of the Peel and Stell families in the 19th Century. The late 18th century baptismal records of Jonathan Peele mention four residences near Keighley: a Paper Mill at Ingrow on the River Worth; nearby Woodhouse; nearby Hainworth Wood; and Lower Holme House near Goose Eye, Laycock - the adjacent Lower Holme Mill was associated with paper-making, including paper for bank notes. Whether Peel's father owned the Mills or simply worked there is not known.

All that is known of Peel's early life is that he used to fish in a stream near Goose Eye [1].

By 1806, his brother John, born eight years earlier, was in Calverley Parish Church marrying a very young Elizabeth Bateson (she could only have been 16½ years old). John Peel had probably established some kind of woollen manufacturing business in Windhill and the eighteen year-old William may have been involved in it. He seems to have moved in the same circles as his brother, marrying John's sister-in-law Rebecca Bateson some time before 1820. The couple's only child, Henrietta Maria, was born that year.

By 1822 both brothers were listed at Windhill as Woollen Cloth Manufacturers in Baines' Trade Directory.

Rebecca died in 1830 aged 34.

On 2 January 1834, a child called Frederick William Peel Bradley was born to a Sarah Bradley, who was a

local blanket

and flannel manufacturer. Given the child’s middle names, it seems likely that he was the son of William Peel.

The clerk at Shipley Parish Church made two attempts to enter the baptism. The first, with a date of 9 February 1834,

appears to show the parents as Peel and Bradley, with the words son of Sarah Bradley added.

This line was crossed out and a fresh entry, with the date 10 February 1834, substituted. It says:

Frederick William Peel, son of Sarah Bradley, spinster.

Frederick William Peel Bradley was a picture framer who never married. When he died in 1887, his Will showed that

he left £917

to two reputed children: a daughter, Margaret Hannah Scholfield [sic], born in 1870 to Julia Fitzgerald

and John Schofield (according to the official Register)

and a son, William Henry Moulson, born (again according to the offical Register) to Jane Simpson and Aquila Moulson in 1874.

Peel next appears as a Burgess in the 1835 Idle Poll, when he voted for John Stuart Wortley to become a Knight of the Shire for the West Riding of Yorkshire./span>

In the 1841 Census for Windhill, he was living with his daughter (Rebecca had died in 1830), his sister Martha Stell and his niece Ann Peel. Ann was a Milliner while the other women were recorded as having Independent Means. Martha died the following year and Ann probably got married in 1844, leaving William alone with his daughter in the elegant Regency residence they called Crag Cottage, as recorded in the 1851 Census. Unusually, the family never had live-in servants.

An historian, writing in the early 1900s, describes the setting thus:

In the early part of the last century when Briggate Windhill was mostly open country with fields sweeping up from the top side of Briggate to Wrose Hill, a man called William Peel, one of the Clothiers of those bye gone days, who by hard work had prospered and made sufficient money to retire on, built a house between Briggate and the Canal which he called Cragg Cottage. In those days there was an open view up the hill to Wrose and from his back view lay the part of Shipley Hall, with a sweeping view up beautiful Airedale, before the large factories of today had been erected and railway come into the landscape [2].

A Short Description of Crag Cottage

No street level photographs of Crag Cottage have been found.

This

image is an extract from an aerial photograph taken in the late 1950s, looking from Pricking Bridge northwards

towards Leeds Road and the old Windhill stations (at the top of the image).

This image is an extract from a 1937 CH Wood aerial photograph looking NE towards Windhill Woodend.

The house was probably built in 1837, Peel having leased the site from Joseph Bateson on 12 August 1834. While the 1838 Township of Idle map does not indicate any structures on the site, the 1847 OS map shows, and names, Crag Cottage. The plot was described in the 1834 Deed as, "adjoining on the North East side thereof to a plot of ground lately sold by the said Joseph Bateson to the Trustees of the Wesleyan Methodist Chapel intended to be erected thereon". Joseph's Will, written on 19 December 1837, suggests that the conveyance to Peel was never completed: "I give and devise unto my granddaughter Henrietta Maria daughter of my daughter Rebecca deceased the house now in the occupation of my son in law William Peel". Should Henrietta predecease him, wrote Joseph, Peel could purchase the house for £150.

Crag Cottage must surely have been the house referred to. If so, Peel only acquired full ownership on 2 December 1863, just 2 weeks after his daughter's death. James Bateson (Joseph Bateson's heir) conveyed to him "All that dwellinghouse situate at Windhill and which was sometime since in the occupation of … William Peel…", presumably for the original sum of £150.

Peel wrote a booklet called A Short Description Of Crag Cottage Windhill And Windhill Crag [3]. It was printed privately in 1857 by SO Bailey, a well-known antiquarian and lithographer, who also did the engravings for the illustrations. Apart from these, and some distant, fuzzy aerial photographs, no images of the house have been found. No plans of the building seem to have survived.

There is no mention of the house's construction in Henrietta Maria's Diary [1], presumably because she was already living there when she began writing it in January 1846. The house was close to the water's edge of the Bradford Canal and a lady of leisure such as Henrietta could sit and watch barges loaded with wool, lime and coal being towed past her window by the canal horses. On 4 January 1846, she noted her shock at seeing a body - probably that of local resident Peter Cowling - being carried to the nearby King's Arms, having just been recovered from the Canal.

Peel's … Short Description Of Crag Cottage … contained a romanticised history of Windhill Crag, with copious - and fanciful - references to its Druidic past. It was laced with rhyming, somewhat orotund verse. There was no indication as to why, how or when he built the Cottage or the odd complex of buildings on the other side of the road. But there are fine descriptions of these, as well as descriptions of some of the more exotic contents of the Cottage, all accompanied by highly informative engravings.

Peel was an antiquarian - the house was stuffed with antique furniture, rare books, valuable paintings and oriental china. This was a man well used to rooting about in dusty attics, attending the jumble sales of the day or bidding at auctions.

Crag Cottage - there is a view of it on an engraving of Briggate on the frontispiece of the Booklet - was a modest building designed in the Regency Classical style. It was symmetrical, with three upper and two lower windows on the façade facing the street. There were no steps up to the central door, which was plain, without the usual semi-circular fanlight. The hipped roof was probably covered in stone slates, while the walls appear to be stuccoed. The only decoration is a kind of awning on at least three sides of the house, in place of the more usual first floor frieze. The ground floor windows and door were edged with shutters that were probably purely decorative.

The garden in the engraving had a lawn with shrubs and an ornamental tree. A strategically placed spinning wheel proves that nostalgia for things rustic is by no means a 20th Century preoccupation. The whole garden was enclosed by a wall topped with railings.

The Dining Room was full of the kind of objets d'art and paintings that a devout late Georgian gentleman might aspire to. The entire room seems to have been designed to give the impression of an altar. A low pedestal table in the centre of the room stands in front of a large chamber organ encased in mahogany and built by Booth of Leeds. The organist would sit at a low keyboard below the organ pipes. The instrument was sold in 1865 to the Shipley Primitive Methodists. Large bibles, one on an eagle lectern, are strategically positioned on either side of this cathedralesque fantasy, which is illuminated by a shuttered window. On the opposite wall stands a rosewood chiffonier supporting a small urn heated from underneath by an oil lamp. On the wall above hangs one of a number of large paintings, most of which appear to illustrate religious themes. This particular canvas, which may depict a disciple genuflecting before Jesus, is reflected in the glass of a large mirror on the wall over the fireplace. Nearby, a crucifix stands on a low table beneath a large painting of an unspecified building. On the floor below is a pair of miniature bibles on stands. The only artificial light in the room is provided by a censer suspended from the ceiling.

Oddly, the one painting that might be expected to appear in the engraving is missing. This, The Incredulity of Thomas, supposedly by Benjamin West [4], was evidently a favourite of Peel's and it receives lavish praise in the text. He reports that the artist's skill in portraying the expressions of the characters and their clothes instils in him a feeling of being in the presence of Christ himself. Quoting lines from the Romantic poet, John Nicholson [5], he suggests that the painting gives life to Christ, just as He gave life to us. This fits in well with one of the philosophical notions of the day - that of Beauty - which suggested that when an object was presented to the mind, it would awaken a train of thought analogous to the character or expression of the original object. The perceived devotion of St John, for example, reflects the veneration that the saint expressed for his master and clearly had an analogous effect on the author.

Peel also wrote about the painting in a pamphlet he published in 1853: The Description of a Painting of The Incredulity of Thomas by that Celebrated Artist, Benjamin West. The text, unfortunately, gives no information on the painting's provenance. It does not say when it was completed. And it does not say when Peel acquired it or how much he paid for it.

After Peel’s de facto bankruptcy in 1865, the painting was sold by public auction to his nephew Charles Peel. When the latter died in 1868, it was auctioned again (as The Unbelieving Thomas) on 1 November 1869 and bought by a Mr Robinson for a respectable £190 [4]. It was shown at the Yorkshire Exhibition in 1875, when the Leeds Mercury's critic described it as "painted after the manner of the old masters but with less inspiration". The painting was later acquired by George Outhwaite Joy, a corn miller from Adel near Leeds, whose son, Alexander Joy, bequeathed it to Leeds Art Gallery in 1919. It is currently (2012) on display at Temple Newsam House, Leeds.

Another painting mentioned in the text, as being "Among the pictures at Crag Cottage" was Anderson's Death of Nicholson [5]. As this picture has not been found in any catalogues, there is no way of knowing what it looked like. However, given the subject matter, it seems safe to say that no painting in the engraving looks anything like a man drowning in a river.

The Astronomical Room appears as a plain, working room high in the rafters of the Cottage. Here are objects associated with the quest for scientific knowledge: globes, a barometer, thermometer and clock; maps & charts on the walls; a diagram of a human skeleton; and, incongruously, a harmonium. The author is shown peering at the sky through a telescope - perhaps the same "very achromatic" Dolland refractor mentioned in the text. John Dollond invented the first achromatic telescope in the mid-16th Century. Peel's telescope, made by Rothwell of Manchester, was perhaps bought from Abraham Sharp's studio at Horton Hall, Sharp being a mathematician / astronomer who was a contemporary of Flamsteed. In this room, immersed in the celestial world, Peel must have experienced a sense of the sublime power of nature, a force he would have ascribed to God, an experience that was possibly more awesome than one gained from looking at a painting.

Billy Peel's Place

The strip of land on the E side of Briggate opposite Crag Cottage and the Wesleyan Mission was originally owned by Jeremiah Kitson, but later became the property of Sammy Cowling, a merchant and Martin Dawson, a farmer.

The land on which Peel built his Roman Church, Vicarage and Observatory

was the south-western part of this area, a close called the Pinnel, which belonged to Dawson.

It was probably auctioned off in 1837 when Dawson was bankrupted. No record of the transaction has been found,

but it may have been purchased by Joseph Bateson.

In his Will, Joseph bequeathed to his son James his freehold estate

“situate lying and being on the north east side

of the house”

(the house he bequeathed to Henrietta Maria Peel – Crag Cottage).

This suggests he owned the land where some or all of Peel’s religious structures were later built.

It is assumed that William Peel purchased the land from James Bateson.

According to the estate agent’s advert in 1837, the purchaser was only able to take full possession

upon the death of the occupant, John Kitson (died in 1840) and also upon the deaths of Martin Dawson

(died in 1853) and his mother, Sarah (death year unknown).

It is not known when Peel built his Church, Vicarage and Observatory. Presumably, it was after 1847: the OS map of that year shows no structures on the site [6].

The buildings were known locally as Billy Peel’s Place

and by family members as Bateson Castle, a strong hint that they were bought by the Batesons.

Peel’s description indicates that there were 3 separate structures: To the north was a Roman Church, with a clock tower topped by a wind vane.

All

these buildings were shown in a rare photograph

(right) taken in the late 1800s [7]. The

Roman Church alone appeared in a photograph in a newspaper article in 1947 [8].

Remarkably, it shows a building that looks exactly as the engraver

depicted it in 1857, minus the wind vane and the clock. The clock, according to the article, had

vanished by the time the photograph was taken.

The building, it says, was once used as a house, but never as a

church. Not

mentioned in the newspaper article, but erected in the grounds of Billy Peel's Place, was a dwelling house

known in the censuses as Peel Cottage (92 Briggate). This is thought to have

become the property of William's nephew, Bateson Peel. When these structures were demolished is not known,

though a photograph of the church taken in 1947 appeared in the Shipley Times and Express that year. Ruin, death, burial William Peel’s involvement with Crag Cottage came to an

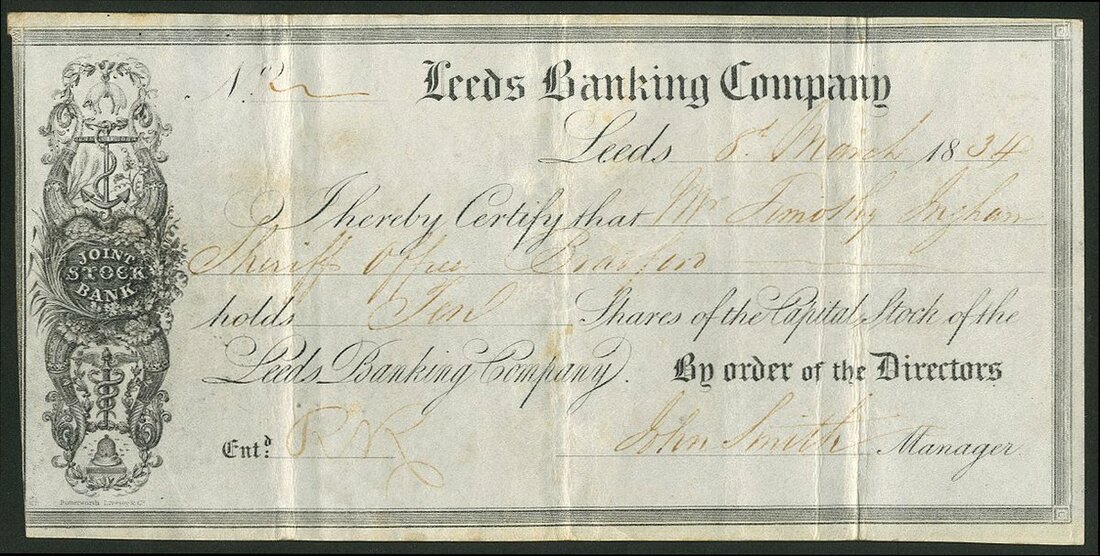

abrupt end in September 1864 when the Leeds Banking Company, in which he owned 50 partly paid shares,

collapsed. With liabilities of more than £2 million, the Bank issued a call on the shares.

As Peel could not oblige, he had to sell all his assets and was ruined.

See details in the

footnotes below

[11].

At the instigation of the official Liquidator, Peel auctioned off the contents of Crag Cottage on 24 and 25

October 1865, then the house itself on 27 November 1865

[9].

The house was purchased by William Bateson and his brother James Bateson the Younger.

Included in the sale was a warehouse containing 2 large rooms being used by the Bateson brothers,

who had a small woollen cloth manufacturing business. 5 cottages or dwelling houses,

together with their respective tenants, were also advertised.

These last 2 items were likely to have been on Plot 211, as designated by the Commissioners of the 1813 Inclosure.

Originally allotted to David Lee, Peel must have bought it, perhaps in the 1830s, and built the 5 houses there,

together with a warehouse and other commercial premises.

In 1866, the manager of the Bank, Edward Greenland, was convicted of perjury and sentenced to 15 months in prison.

18 months later, Thomas Edgeley, a merchant, was convicted of fraud against the Bank and jailed for 21 months

with hard labour.

It

came too late for William. He had gone

to live at Kildwick, probably with his grand-nephew John Stell, but only

survived the crash two years, dying there in early 1867, aged 78. He was buried

in the family vault at Shipley St Paul's Church.

Before the clearance, Shipley Council recorded, in no particular order and not always accurately,

the inscriptions on the gravestones. For graves numbered 206 to 208, three stones from the Peel vault

were transcribed thus:

There

was no mention, either in the adverts or in the 1866 conveyance documents, of

the sale of Billy Peel's Place, that

complex of odd buildings on the east side of the main road. However,

an 1869 sale catalogue for adjacent plots of land show that James Bateson owned

the land on which the Roman Church was built Peel

probably owned a small plot of land of 140 sq yds immediately south of a

footpath leading to Peel Place (where the Owlet Nursery now stands). The plot

was included in the 1964 sale of Crag Cottage to Shipley UDC. Peel

also owned a small plot of land of 896 sq yds he bought in 1852 at Woodend.

Described as part of the Long Field, the plot has not been positively

identified. To the N of Leeds Road, it was bounded on the N by Capt Duncombe's

land, to the E by John Rhodes' land and to the W by the rest of Long Field,

owned by Joseph Dawson. Crag

Cottage having passed into the hands of William and James Bateson, William was

listed as living there in the 1881 Kelly's Directory; the 1891 Census places

him at Crag Cottage, with his wife Esther; and he was listed as a Gentleman of

70 Briggate in the 1893 Post Office Directory. When William died in 1892, his

address was Crag Cottage. By the time of the 1901 Census, his widow had moved

to 102 Briggate. In 1893 and 1894, Crag Cottage was occupied by Johnson Dove. A

John Riley took it over in 1895 and 1896. No voters were recorded at No. 70 in

Parliamentary or Council elections between 1896 and 1902. In 1902 and 1903

Henry Bailey was in residence there. When

Esther died in 1905 it is likely that Crag Cottage was bequeathed to her

daughter Isabella Stancliffe [11]. From

1905 to 1917 the

family

occupied Crag Cottage. Her sons Henry James &

Charles Frederick Stancliffe were registered there from 1919 on. By 1930,

Charles had moved to 7 Cowling Road, Windhill, while Ethel, Mary, Henry and

Isabella remained at No. 70. They were still there in 1935. Isabella

died in 1937 and left Crag Cottage to her son Charles Stancliffe [probably -

probate was granted jointly to Walter Harris, husband of her daughter Gertrude

and Charles]. Charles

did not live at Crag Cottage and may have let it to Ethel, Mary and Henry, who

were registered there in 1940, 1945 and 1948. Henry disappeared from the record

after 1948. From 1949 to 1962 Ethel and Mary occupied No 70. The

last 5 or 6 years of their residence would not have been pleasant - Shipley

Urban District Council obtained a Slum Clearance Order for Briggate in 1955 and

probably began demolition the following year: much of the southern part of

Windhill Crag would have resembled a bomb site. To the north the Wesleyan Mission

closed its doors in December 1961; its sale to the council was concluded in

1963 and it was probably demolished shortly afterwards. It was replaced, like the

rest of the western side of Briggate, by a wooded, landscaped slope. Both

Stancliffe spinsters died in 1962 - Mary in March and Ethel in October. It is

likely that Crag Cottage remained unoccupied and derelict for the next two

years while Shipley UDC continued its slum clearance programme. Charles

Stancliffe entered into negotiations with the Council and sold Crag Cottage on

7 February 1964 for a paltry £765. References and Notes

Throughout this document, quotations and transcriptions have been written in italics. [1] see extracts from her Diary in

this transcription of a Memorial of Henrietta Maria Peel, Crag

Cottage, Windhill published in Bradford in 1864, taken from one of two copies

in Bradford Library's collection. A download of a copy held by the British Library

(and published by Google Books) was used to make the slide show in the

Document Scans section. Leeds City Library also has a copy listed. [2] from A

Windhill Romance And Tragedy, by William

Williams (Chairman of Baildon Urban District Council in 1915) [3] A

Short Description Of Crag Cottage Windhill And Windhill Crag, by William

Peel, 1857. The print run is thought to have been around 400. At least 7 copies are extant:

four in private hands

(incl WP127 and WP389); one in the British Library/Museum (WP324, published by Google Books); one in Bradford City Library;

Leeds City Library has a copy listed.

[4]

Benjamin West (1738 - 1820) was an American-born painter of historical,

religious, and mythological subjects who had a profound influence on the

development of historical painting in Britain. He painted for the British Royal

family and, with Sir Joshua Reynolds, was a founder of the Royal Academy,

becoming its president in 1792. Some modern critics regard West's figures as

somewhat stiff, his colours harsh, and his themes uninspired.

At the end of an auction of 160 of West's paintings and drawings at his Newman Street Gallery, London over 3 days in May 1829,

the average price paid was around 80 guineas.

The Incredulity of Thomas was not among the lots. Nor was it shown at an 1824 exhibition of 141 of West's works at the

Gallery.

It may, of course, have already been in private hands, but the following facts add to

doubts about the painting's attribution:

It is not mentioned in academic studies of Benjamin West seen by this author.

It is not listed in John Galt's A Catalogue of thee Works of Mr. West

(in Appendix II of his The Life, Studies, And Works Of Benjamin West, Esq., published

in 1820). Peel must have known this, because he was familiar with Galt's publication - it was the source of

large parts of his 1853 pamphlet The Description of a Painting of The

Incredulity of Thomas by that Celebrated Artist, Benjamin West.

In the biographical section of the pamphlet (entitled A Sketch of the Life of Benjamin West), 8 of West's works were mentioned by name.

Oddly, given the subject of the pamphlet, The Incredulity of Thomas was not one of them.

It is not listed in a definitive catalogue raisonné entitled The Paintings of Benjamin West published in 1986

by Helmut von Erffa and Allen Staley.

It is mentioned in an index to the collection of papers compiled by these two authors, an archive maintained by the Historical Society

of Pennsylvania. Unfortunately, The Incredulity of Thomas is listed in a section entitled

Rejected Attributions:

von Erffa and Staley did not, apparently, believe that the work was painted by Benjamin West.

The painting was bequeathed to Leeds Art Gallery and is currently on display at Temple Newsam House.

The Gallery has stated (personal communication, 2010) that it has no information on the painting's provenance prior to 1919, the year of acquisition.

[5] John Nicholson (1790 - 1843) was the son of

a worsted manufacturer. His education

at Bingley Grammar School taught him how the world of sentiment could be

expressed in poetry. As a lowly

woolsorter, he is said to have composed his poems in a mill woolshed and

believed his was an authentic working-class voice. He styled himself The

Airedale Poet and was immensely

popular in the 1820s and 30s. Nicholson

was famously drowned on Good Friday 1843, when he fell into the River Aire

whilst drunk.

The painter of Death of Nicholson was probably John Wilson Anderson (1798 - 1851), who is known for his 1825

painting of one of the earliest views of Bradford. He is also known for his wife Hannah, who died, probably by suicide,

of arsenic poisoning in 1837. [6] although there is a Memorial to an Indenture

at Wakefield recording a conveyance between Sammy Cowling and Peel in 1842,

none of the plots of land listed had a frontage onto Briggate. And the 1847

Tithe Map still shows Cowling as the owner of the plots. [7] Shipley through the Camera, by M

Crabtree, published by Hanson & Oak, 1902 [8] from a Bradford Telegraph & Argus

article dated late 1940s or early 1950s, published in A Windhill Romance And Tragedy, by William Williams [9]

The contents of Crag Cottage were advertised as follows:

Antique oak furniture:

[10] Bradford Family History Society, in its 2009

memorial inscriptions project wrote: “When the Churchyards were finally closed, Shipley Urban District Council

took over their maintenance. An early move was to record the monumental inscriptions and move/remove many of

the stones to enable easier cutting of grass.”

[11]

[12]

Isabella Bateson married William Stancliffe in 1875. They had at least 9 children. One - Clara - died in infancy. Three - Mary, Henry and Ethel - did not marry. Esther, born in 1877, married George Firth in 1805. She may have died in 1946 in the Bradford area. A son, Arthur, was born in 1905, married in 1938 and died in 1986. John, born in 1880, enlisted in the 19th Hussars in 1902.

To the south, set back from the road, was a “rustic … vicarage” with an inscription above the door.

Adjoining the Vicarage was an Observatory with another clock tower that held a clock (dedicated to Sir Robert Peel),

an inscription and a sundial.

The Church and the Observatory tower were solid buildings but the Vicarage and the structure to the south of the

Observatory were almost certainly facades. Houses appear to have been built behind them.

The vault

Along with many other tombs, the vault was removed during landscaping works undertaken by the local Council

in the late 1950s and disappeared without trace. It is thought to have been located in the original,

Upper Graveyard, close to the east door [10].

"In this vault rest the remains of WILLIAM PEEL of Windhill who departed this life

December 30th 1866 aged 78 years.

In this vault rest the remains of REBECCA PEEL wife of WILLIAM PEEL who departed this life April 1st 1850

aged 55 years.

[Also the remains of someone illegible.]"

Rebecca actually died on 1 April 1830 aged 34.

The illegible sentence probably refers to Henrietta Maria,

who died on 19 November 1863.

Also recorded, against Grave 216, was: "WILLIAM PEEL, Crag Cottage. Owner."

In the 1930s, Arthur Blackburn transcribed the following from the Peel tomb:

"531 PEEL

In this vault rest the remains of WILLIAM PEEL of Windhill, who departed this life Dec 10th 1866, aged 78 years.

I WAIT FOR THY COMING O LORD".

Peel actually died on 30 December 1866.

Curiously, neither Rebecca nor Henrietta Maria Peel were mentioned.

One further curiosity may be of interest: in Henrietta Maria Peel's Memorial,

published after her death, is a

drawing of the vault

(between pages 50 and 51). It contains a handwritten inscription. Some of this is

indecipherable, though the last line, which obviously refers to Henrietta herself, gives her date of death as

NOV 19 1861, rather than 1863.

Property

pair of carved high-back chairs

clock in open case

spinning wheel

hall table

church reading desk with lamp, stand and cross and attached Bible (black letter folio)

mantlelpiece and panelling

Paintings:

the

Incredulity of Thomas by Benjamin West

Philosophical apparatus:

4-feet reflecting telescope by Jones of London

42-inch achromatic telescope by Rothwell of Manchester

20-inch reflecting telescope

quadrant in mahogany case

sector, mahogany, mounted on stand

Library of Literature: containing many rare and valuable works

Miscellaneous items:

oriental china, grey beard, antique puzzle cup, leather bottle, copper rain gauge

Large Organ:

by Booth of Leeds - mahogany case, compass GG to F in alto, 58 notes; No 1 open diapason, 58 pipes; No 2 stop diapason bass; No 2 stop diapason treble, 56 pipes; No 4 dulciana fiddle in G, 35 pipes; No 5 principal, 58 pipes; No 6 twelfth, 58 pipes; No 7 fifteeth, 58 pipes; No 6 bassoon, 58 pipes; blows by hand or foot

Other instruments:

rosewood cottage pianoforte, finger organ, barrel organ in mahogany case, brass trumpets

The Modern Cabinet Furniture:

Spanish mahogany sideboard

chair sets in hair-seating

dining, loo tables, small tables

crimson damask window curtains, brass pole cornices

Spanish mahogany chaffonier [sic]

rosewood music stool, pair of foot ottomans

Brussels carpets

chimney glasses in gilt frames

Spanish mahogany Arabian bedstead and feather beds

chests, drawers, bookcases, toilet glasses, towel rails, washstands, toilet tables, kitchen furniture,

culinary utensils etc

Known buyers:

the organ was bought by Shipley Primitive Methodists - Bradford Observer 30 Nov 1865.

The Rothwell telescope was knocked down to Amos Bairstow - Bradford Observer 26 Oct 1865.

The

Incredulity of Thomas was bought by Peel's nephew, Charles Peel.

The Church historian thought the vault may have been in the Lower Graveyard (to the north of the Church)

on the grounds that the area became available for interments after 1860 (personal communication 27 Feb 2019).

However, the Peel tomb is not visible in this fine, coloured

photograph of the Lower Graveyard, which was published as a postcard in 1902-03; the original black and white image was made in 1893

and is in the Francis Frith Collection.

Peel would almost certainly have reserved the plot for the tomb long before 1860 and may well have constructed it

in the 1850s as a repository for his wife Rebecca. It was certainly built by 1862, because Henrietta wrote

(see her Memorial, page 19): "My Father had the vault opened and the lead coffins placed there".

This means that the vault would have been in the original, Upper Graveyard on the south side of the Church.

The theory was confirmed when this

photograph

was published (in 2022) as a frontispiece to the Church's new

history website (www.stpaulsshipleyhistory.org/). Taken circa 1910, it shows (circled) the Peel vault on

the south side of the church, close to the east door, where a bench is currently placed.

The only surviving tombs in the vicinity are a monumental memorial to Agnes Sharp and one to Rev William Kelly

and family.

The Leeds Banking Company collapse

The fraud

The Bank opened in Albion Street in 1832 and drew its investors solely from the Leeds area. Edward Greenland was its manager

from 1842 and perhaps earlier. Timothy Ingham, the owner of this example of its share certificate,

was a gentleman from Ilkley.

One of the frauds involved a fictitious timber outfit called the Maydampeck Forest Company of Servia

(Serbia).

Located on the banks of the Danube, it was supposed to export timber to England.

Large numbers of forged bills of exchange were drawn on the company

and sent by an intermediary, Edgeley & Co, to Greenland for discounting. Edgeley & Co would then be credited

with the value of the bills. When payment on the bills became due, Maydampeck would simply issue further fake

bills to cover the deficit. In effect, the Bank was advancing funds to a company without assets, without security.

It was said to have lost £108,000 to the fraud: "..with the quickness of the magician's

wand," Edgeley "created boundless wealth in Servia...and as the Leeds Bank was in hard straits at the time,

it only required very little persuasion to induce the manager to accept £61,000 worth of bills..."

[York Herald 20 June 1868].

In a related case, a Leeds ironfounder called John Woodhead Marsden passed through the Bank forged bills of exchange

totalling £80,000.

Marsden was a well-known mountebank - his fellow ironfounders used to buy castings from him because they cost less than

they themselves could make them for. Accordingly, "his downfall has long been expected" [Sheffield Daily Telegraph 24 Sept 1864].

Marsden was said to have absconded to New York in October 1864 onboard the SS Etna (with the Leeds police in hot pursuit)

and was never tried.

Marsden's cashier, Thomas Scaife, was arraigned in his stead and was convicted on 13 December 1864 of forging & uttering falsities.

He was sentenced to 15 years and, after a failed appeal for clemency to the Home Secretary, was transported to Freemantle, WA onboard the convict ship Belgravia in 1866. The voyage took 88 days.

Pardoned in 1874, he died on 26 July 1896 [Western Australia Convicts group 2025].

Despite cooperating fully with the enquiry, the lowly Thomas Scaife appears to have received much harsher treatment than was meted

out to either Edward Greenland or Thomas Edgeley (see below). It is interesting to note that he was actually an apothecary by profession. How he came to be Marsden's bookkeeper and cashier is not known.

Edward Greenland was suspected of being involved in the fraud, that "he knew all about it",

but strenuously denied this. An investigation by a committe of the bank's shareholders found that he

had been poorly supervised by the directors and had behaved recklessly rather than fraudulently [Leeds Mercury 1 Oct 1864].

Greenland had lost control of the fraudulent accounts and tried to cover up the Bank's losses.

According to the Melbourne Herald of 12 Nov 1864, he had no alternative but "to go to the renewals,

relying upon accidents to bring the accounts right". In early 1867, after a private prosecution brought

on behalf of the inhabitants of Leeds, he was convicted of falsifying most of the returns made to the

Inland Revenue regarding the notes he had issued. He was jailed for 15 months [Leeds Mercury 31 Jan 1867].

During the sentencing hearing, a medical report was presented stating that Greenland was so ill that were

he to be "deprived of nourishing food and occasional stimulants, and of the comforts of life to which

he has become accustomed, it would cause his death".

Regarding Greenland's "comforts", the day after the contents of his house in Leeds were auctioned on 7 and

8 December 1864, his wine cellar came up for sale. It included 150 dozen bottles of fine wines, ports and spirits

[Leeds Mercury 2 Dec 1864].

In a settlement disclosed in the Leeds Mercury of 8 Aug 1865, it was revealed that Greenland had sometimes received

bonuses of £1000 from the Bank. He agreed to pay compensation for negligence of £6000.

Greenland must have had friends in high places: the Home Secretary granted him a free pardon because of his age

and ill health and he was released after serving only 6 months.

Parliament was outraged, noting that:

“...the failure of the Leeds Banking Company … had been attended by some of the most frightful consequences

that had ever been known to result from a similar catastrophe..." Hundreds of families were reduced from a

state of prosperity to absolute destitution. "Of 243 shareholders at the time of the failure, little more

than fifty were now able to meet the calls made upon them; twenty-five had died, some from distress of mind,

some by suicide; while some of the shareholders had lost their reason, and were now confined in lunatic asylums.

It was believed that all this was owing to a long course of reckless extravagance, and even criminal proceedings

on the part of Greenland the manager.” [Hansard Vol 189, 5 Aug 1867: Case of Edward Greenland].

Greenland's health was so poor that he lived to the age of 82, dying in Geneva in 1878.

On 13 June 1868, Thomas Edgeley was convicted of fraud against the Leeds Banking Company and sentenced to

21 months with hard labour [Liverpool Mercury 16 June 1868].

The shares

The Leeds Banking Company ceased trading on 19 September 1864 and was wound up on October 18.

The Liquidator, William Turquand, announced that 194 shareholders in their own right would have to make good

to the creditors of the Bank a deficiency of some £500,000 [Leeds Mercury 16 Nov 1864].

Before the crash the shares were said to be worth £900 each. Peel owned 50, though they were only partly paid.

He would have been a very wealthy man - on paper at least.

On 28 Mar 1865, Turquand called for £70 per share to be paid by liable shareholders.

A further call for £40 was made on 11 August 1865. Peel's liability was assessed at 10 shares,

meaning, presumably, that his other 40 shares were fully paid up.

His total liability would therefore have been £1100.

By 7 Sept 1866, the creditors had received a dividend of 14s in the pound.

Insolvency

In September 1864, when the Bank crashed, it is likely that Peel was already skint and up to his ears in debt.

On 2 December 1863 he had purchased Crag Cottage from James Bateson, possibly for the discounted price of £150,

as mandated by Joseph Bateson's 1837 Will.

Ten months after his daughter's death in November 1863, he would have spent money on printing her Memorial book

and on the design and manufacture of her Memorial Window in Shipley Parish Church.

Installed by August 1864, the 3 light window would likely have cost £200 or so.

For comparison, the 5 light South Chancel Window, installed in Bradford Cathedral in 1864,

cost £300 [www.bradfordhistorical.org.uk/morris.html: The Morris Windows in Bradford Cathedral].

After the crash, when the shares he would have used as collateral became worthless,

his lenders probably called in their loans.

On the plus side, Peel sold a share of the Forester's Arms Inn and associated properties in

December 1863 and April 1864.

In the months after the crash, Peel would have feared bankruptcy, knowing that a neighbour, George Wilcock,

had been made bankrupt in 1848 (with debts of £779), imprisoned briefly and only discharged in 1865 [Leeds Mercury 17 June 1865].

When he died in 1884, Wilcock left only £29 15s.

Although there are no records that Peel was declared bankrupt, it seems clear that he was an insolvent debtor,

obliged by the official Liquidator to put Crag Cottage and all its contents up for sale in October and

November 1865 - the Memorial of the sale gives the official Liquidator as one

of the interested parties.

While it is not known how much the Batesons paid for Crag Cottage (the Memorial did not mention the price,

in line with common practice), an estimate can be made based on the price

of a house sold 45 years later. This was Greystones, a large Edwardian semi that

was built near Baildon Station, just across the Aire valley, in 1909. House prices had stagnated and even declined

over the previous 50 years, so the price paid, £918, might have been similar to the price of

an equivalent property in the 1860s.

Accordingly, it is thought that a fine, detached house such as Crag Cottage could easily have fetched £1000 at auction.

It might have helped Peel avoid bankruptcy, but would have left him with nothing.

The fact that Peel's Will, presuming he wrote one, was not made public suggests that there was no

value in his estate when he died at the end of 1866.

Stancliffe family history

notes

Discharged on medical grounds in 1908, he spent 10 months as a patient

at High Royds, Menston 'Lunatic' Asylum.

Diagnosed with 'Melancholia', he suffered from depression,

hallucinations and suicidal tendencies. Whether this was shell shock or some

other trauma brought about by military service is not known though his friends

are said to have blamed 'army neglect' for his illness.

Fortunately, he was discharged in February 1909 and declared 'recovered'

a month later. In March 1915 he sailed to St Johns, New Brunswick and

immediately enlisted in the Canadian Over-seas Expeditionary Force.

He married Laura Deswell in the last quarter of 1915 in Bradford.

He survived the War and, in February 1923, sailed again to Canada,

intending to settle there permanently. He was a Cook.

His wife followed in June that year. In July 1924, they returned to live

in Windhill. John died in 1953 and Laura in 1962.

The couple appear to have had no children.

Gertrude, born in 1884, married Walter Harris in 1908.

She died in Saltaire in 1970.

No children have been found.

Arthur was born in 1886.

A Carpenter, he sailed to Philadelphia in March 1910.

By 1913, he was back in Yorkshire marrying Annie Bell on 17 June at Baildon Parish

Church.

On 18 June, the couple were onboard the SS Merion, travelling to

Jamestown via New York.

Their only child, William Bateson Stancliffe, was born there in 1926 and

died in 1986.

The family sailed to Liverpool in 1932 but it is not known when Arthur

returned to Britain permanently.

He died in Bradford in 1962, but is commemorated on a grave in

Chautauqua, New York state.

Charles was born in 1888.He may have served in the Royal Army Medical

Corps during the War.

A Shop Manager, he married Hannah Thorpe in 1922 and had at least 7

children, four of whom died in infancy.

Another son, Charles, died at the age of 23.

A daughter, Dorothy, married in 1967 and died in Cambridge in 1971.

The youngest child, born in 1935, married in 1965.

Charles himself died in 1975 and Hannah 3 years later.

© Windhill Origins